Learning from video games

CORRECTION: In this article I make that case that Mario's name is just Mario, not Super Mario. Hacker News user bitwize pointed out that in certain games Mario's bigger form (the form he turns into after picking up a Super Mushroom) is indeed referred to as Super Mario. I stand corrected (thanks bitwize!)

In 2005, Steve Jobs told the graduating class of Stanford a now-famous story about connecting the dots - a story about the calligraphy courses he took in his college years, which later influenced the industry-leading digital fonts that shipped with the Macintosh. He said:

Again, you can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something — your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever. This approach has never let me down, and it has made all the difference in my life.

I’m a firm believer in this idea. I think every experience - even ones that seem frivolous - can teach you something valuable if you’re willing to pay attention.

In the spirit of connecting the dots, I’m writing a series of articles about useful truths I’ve picked up in unlikely places. I hope they not only entertain you, but perhaps compel you to consider what you could learn from your own adventures!

I’m a gamer. I wouldn’t call myself a capital-G Gamer, but I do enjoy playing and talking about video games when I have time, and as I've progressed into adulthood I've found I also really like thinking about them as well.

At some point I realized I often rely on mental models that I first developed playing a video game (I'm sure someone's written a thinkpiece in The Atlantic about what this means for my generation.) Something that I think is special about the medium is that when you're learning, you almost always are learning by doing. You pick up new techniques and frameworks because you have to in order to win the game (which is usually something you really want to do), and in my experience, putting ideas into practice in high-stakes situations is a great way to understand them on a more visceral level.

So, I urge you - if you too want to learn from video games, try them out! Get your hands dirty. You don’t have to be an expert!

Learning from platformers

I don't need to tell you what a platformer is. It's probably the first thing that popped into your head when you read "video game": Mario running around, grabbing mushrooms, and stompin' on Goombas. Platformers are one of the most popular genres of game, and for good reason - they're casual, accessible fun, easy to pick up and understand. They're also a hallmark of the earliest era of home gaming, when video games went from being a weird pinball-machine thing you could play at the bar to being a weird toy computer you could plug into your TV.

It can be really instructive to play some older games. The more popular ones have been ported to newer consoles, but you can also play them on an emulator (IF you own a legitimate physical copy of the game of course and far be it from me to ever suggest you use an emulator in any other capacity.) Back in the day, if you wanted to market a successful video game, you had to be an incredibly efficient communicator, as well as making something really fun. Your customers were usually children - not known for their powers of attention - and you needed to make sure they understood what the controls were, understood what the point of the game was and were excited and engaged within the first ten seconds of picking up the controller. There simply wasn't enough memory available to include a drawn-out tutorial with lots of writing, and you couldn't count on the manual either - no kid is going to sit down and read a booklet about the amazing new game they got for Christmas. The only option is to somehow incept knowledge into the users's brain as they play.

The poster child for this kind of approach is, of course, Mario. You may be familiar with this video, or others like it, which showcases all the different ways the game communicates with the player without resorting to text.

Before we go any further, I need to clear up something very important.

Mario Bros. - the very first one - was an early Nintendo release about two plumber brothers who had to rid the sewers of turtles and crabs and weird moths. You wouldn't recognize it unless you're big into old arcade games. It was not originally developed for Nintendo's famous home console, the Family Computer (Famicom for short, and known stateside as the NES), which debuted almost simultaneously in July 1983 (it would soon be ported over, however.)

In 1985, after a few years of experience making games for the Famicom, Nintendo felt ready to begin work on a platformer that would push the bounds of the genre. The Famicom port of Mario Bros. was selling pretty well, so the development team decided to reuse the IP for their new game. It had little in common with the first Mario Bros. besides the name and the characters, so instead of calling it Mario Bros. 2, they named it Super Mario Bros. Every mainline Mario game thereafter has carried the same epithet, for reasons unknown; perhaps it just has a certain ring to it.

In any case - it's Super (Mario Bros.), not (Super Mario) Bros. His name's not Super Mario. He's just a regular Mario in Super games. Thank you for your attention to this important matter.

I don’t know about you, but I can’t remember learning to play a single Mario game, not even the later ones. I obviously wasn't born knowing how so it must have happened at some point, but I remember playing the game more than controlling the game. In other words, there was no space between me wanting something to happen on the screen and me making it happen - the act of controlling was so smooth that most of the time I wasn't aware I was doing it, and my goal was always clear enough that I was never just sitting around trying to figure out what the game wanted from me. This wasn't an accident; it was the result of hundreds of tiny design decisions that were individually invisible, but which combined to produce the feeling of graceful simplicity that is Mario's calling card.

If you have the time, try picking up a few platformers you haven’t tried before, without reading the manual or looking up anything about them online. Come in completely fresh. Pay attention to how the first thirty minutes feel - are you confused? Are you bored? How much can you experiment? What is the game trying to tell you about how to play it, and is that getting across? What, if anything, is making you want to play more?

After that, try picking up some more modern, big-budget games. What’s changed about those first thirty minutes? What’s stayed the same? What new assumptions do the developers seem to be making about their players? Are things better now, or worse, or just different?

Something else I think is really interesting are the ways that platformers have modernized over the years, and I can't think of a better example of a modern platformer than 2018's Celeste. Celeste is a gem; besides being stylish, innovative, and beautifully constructed, it just feels great to play. Again, not an accident!

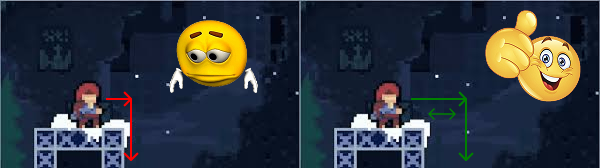

Celeste has a lot of little tricks that add to its polish, and one of the coolest is called Wile E. Coyote time, named after the trope where cartoon characters run off a cliff and don't start falling until they look down. There is a small period where you can jump after leaving the ledge - like the wayward coyote, you're basically jumping on thin air. The window is so small that you won't notice it if you don't know about it already; it affects how the game feels, instead of being a mechanic you can consciously use.

Play an older game without Wile E. Coyote time (like the first Super Mario Bros.) and you may find that it tends to eat your inputs when you try to jump a gap (but it isn't actually eating your jumps, of course - you're just pressing the button a split-second too late.)

Super Mario Bros. is fair but it feels unfair. Celeste is a little unfair in the player's favor, and it feels fair! Perception is weird and can be very disconnected from reality (consider, for instance, the Lynchian sinkhole that is color theory.) If you're creating software, games, art, or music (or, frankly, anything else that can be perceived) you may have to include some strange quirks or adjustments to make things feel normal to the human on the other side.

The overall lesson, I think, is that you always, always have to hold yourself accountable to the end user experience, in its totality. There just isn't a substitute.

Learning from roguelikes

Rogue was a dungeon-crawler from the days when many games made do with ASCII art in lieu of graphics (the zombies in Rogue were easy to spot because they were all Zs.) Its inclusion in BSD 4.2 gave it wide distribution; it not only ended up a cult classic, but its unique mechanics and gripping gameplay spawned a whole new variety of game, aptly called roguelikes. Roguelikes have steadily grown from a niche genre to something of a mainstay, with high profile hits like Balatro (a solo project which ended up on the shortlist for 2024's Game of the Year and has an Apple Watch port), Hades, Slay the Spire, Nubby's Number Factory (this is a real game that just came out on Steam, I didn't make it up), and many more.

In a lot of respects a roguelike plays like a more "traditional" game. You overcome a series of challenges, defeating enemies and bosses as you go, and facing down a super-powered final boss at the end. Like traditional games, the difficulty increases as you progress. And like (some) traditional games, you can make yourself stronger by purchasing better equipment, spells, boons, etc. after every room, stage, or boss fight.

What's no so traditional is that you have one shot, and if you die you have to start all the way over. This might sound really boring and frustrating, but roguelikes make this mechanic work in a few important ways. Many parts of these games are randomly generated (the room layouts, for example, and/or the choice of items at the shop), so if you die and have to restart you won't have to play through the exact same game again. They're also pretty short - you can complete a typical run in an hour or two once you get good enough to win. Finally, most roguelikes have special upgrades that make your character stronger permanently, not just within a single run. As you play the game and find more of these upgrades, your baseline strength slowly increases, which makes things a little easier.

Crucially - the expectation is not that you will play through the entire game perfectly as a scrawny weakling who can't take a hit. During any given run you have a lot of opportunities to make your character stronger in a lot of different ways; picking the right gear to craft the perfect loadout is pretty fun, and a big part of any roguelike's appeal.

Roguelikes can feel crushingly difficult at first, especially if you're not familiar with the genre. Skilled gameplay is necessary but usually not sufficient; your adversaries gain power so quickly that they're soon undefeatable if you don't upgrade yourself. But even that's underselling the challenge a bit, because in most roguelikes the difficulty ramps up superlinearly - the bump between stages increases instead of staying the same. If you make your character better by a constant amount every time you visit the shop, they'll get stronger in a linear fashion, which means you'll fall behind and lose. You have to get creative.

Now I get to talk about one of my favorite topics, which is nonlinearity. Many of the day-to-day parts of our lives are linear. You put in a certain amount of work and get a certain amount of money in return, determined by some conversion factor. Then you exchange some of that money for a certain amount of food, which gives you a certain amount of energy when you eat it. Your clean your living area after a certain number of days to get rid of a certain amount of mess, which accumulates at a basically constant rate.

On the other hand, many of the broader systems that we live in are highly nonlinear. They have lots of moving parts and forces that dampen or reinforce each other in very specific ways. In my experience, the most effective ways by far to make things happen (whether that be making money, effecting change, self-improvement, etc.) all involve something nonlinear - usually a strong feedback loop (and often more than one.)

Roguelikes are all about finding and exploiting nonlinearities to keep up with the nonlinear difficulty curve. The way to win is to create positive feedback between different parts of your build (this is often referred to as "building an engine".) For example, many roguelikes have shops that lets you buy items and abilities, and these shops usually take gold that you get from progressing through the game. There are often options to take on more challenging or risky paths in return for more gold...but these are difficult to clear if you have a weak character. It's usually a good idea to try to get an upgrade that gives you extra gold as soon as possible. Then, you can use the surplus gold to buy better stuff, which will let you take on harder challenges, which will give you more gold, and so on.

If you're able, get into a roguelike (I recommend Hades or Balatro if you're not sure what to pick) and try your best to get good at it. I've found that when you play for long enough you slowly develop an intuition around which combinations of items will give you momentum and which are going to flatline. You can feel, on a pretty visceral level, when your build is thriving and when it's stalling out. See if you can beat the game, and if you do, reflect on how you did it. How repeatable is your approach, and why do you think that is? You may notice that your strategy looks somewhat arbitrary from the outside - that it seems to hinge on random minutiae. Nonlinearity will do that; it has a way of making many details insignificant and a handful all-important.

For example (and if I may bust out my little soapbox for a minute) - there's nothing wrong with building small(er) startups (done right, even a "modest" exit can be a life-changing event for you and your employees), but if you want to be a truly generational company (i.e. decacorn or above), differentiation, in my opinion, is ten times more important than anything else - even (especially) in the very beginning.

No matter what kind of company you're building, you need a compelling answer to the question "why you?" What makes you stand out? Why should people trust you instead of the other guys, who are cheaper/bigger/more full-featured? Differentiation is extremely important because it's a non-linear factor - it's very hard to gain marginal differentiation when you're small because your audience doesn't know who you are and doesn't have any reason to listen to you. You have to fight for mind share. As you get bigger and more successful, people begin to recognize your brand, and it becomes easier to get their attention and educate them about why you're different, which helps you grow even bigger, etc.

Why is everyone always talking about OpenAI? Because they’re big and famous. Why are they big and famous? Because they made ChatGPT. Why did so many people try ChatGPT? Because it was made by OpenAI and people had heard of them. Why had people heard of them? Because Elon Musk and Sam Altman were involved…and so on.

Standing out helps you get big, and being big makes you stand out. It’s a feedback loop.

On the flip side, if you ignore differentiation and spend all your time on linear factors, like:

- Going to conferences and getting the word out

- Developing the product

- Raising money, getting an office, and setting up other infrastructure

People will hear about you, but they won’t remember you, because there’s nothing distinguishing you from the other hundred startups they heard about that day. This makes it harder to grow, so you’ll stay small. Then, when people see that you’re small, they’ll think “huh, I haven't heard of them and they seem pretty small; they might not even be around in five years” and they’ll forget about you. It’s a vicious cycle.

If it isn't clear by now, I think having a nose for nonlinearities is extremely useful. If you want to start building that particular muscle I'd encourage you to pick up a roguelike - you might be surprised by how much you get out of it!

Learning from farming sims

If you were playing games in the 90s you probably remember Harvest Moon - a charming game for the Super NES where you play as a farmer and do farming things on your farm (this may come as a shock but I haven't played Harvest Moon.) Eric Barone (also known by his screenname, ConcernedApe), who in 2012 was working as an usher in Seattle while he searched for game development jobs, also remembered Harvest Moon. He began work on Stardew Valley as a side project that was meant to address some of the shortcomings he saw in recent installments of the series. 2016 saw the first release of the game, which was met with overwhelming critical and commercial success, and Barone has continued development work since then (version 1.6 was released in 2024), mostly by himself.

In Stardew Valley, you play as a twenty-something who has just discovered that their late grandfather left them his farm in the countryside. You quit your job working for a thinly veiled caricature of Amazon, leave the bustling city, and head off to live a reflective, pastoral life in a secluded valley. Stardew has a widespread reputation as the quintessential “cozy game”, perfect for people who just want a peaceful way to unwind. However, for a certain class of player, Stardew Valley is extremely serious. These daring souls want to see every piece of content it has to offer (and there's such an overwhelming abundance of stuff to do that this can take hundreds of hours.) The game is lots of fun no matter how you play it, though, and you certainly don't have to turn over every single stone to have a good time. You don't have to...but what if you did?

Committing to greatness reveals the true scope of Stardew's maximalist underbelly. To become the Ultimate Farmer you have to catch every type of fish, raise every kind of animal, cook every recipe, mine down to the center of the earth, be best friends with everyone you meet, get married and have children, and - most importantly - make fifty million dollars. Yeah, your grandpa gave you his farm, but after three years his Ghost returns to see if you made the most of it, and if he's not satisfied he casts you into hell! (Just kidding. I think he just shakes his head or something.)

It's exhilarating to push Stardew to its limits like this, and it also changes the dynamics of the game quite a bit, especially when you focus on maximizing your money:

-

If you've ever felt like you didn't really get the concept of cashflow, going for max earnings in Stardew Valley is an excellent way to understand it better. Managing your cashflow is an extremely important component of this game, especially early on.

There are a few ways to make money in Stardew - you can farm, you can raise animals, you can catch fish, you can forage, you can do jobs for people, or you can mine jewels. The one that can scale up immediately is farming - you can grow as many crops as you can plant and water - but you have to buy the seeds first! In Stardew Valley there are a lot of ways to turn a profit by investing some money for a while, and planting crops is one of them - when you'll sell the crops, you'll end up with more money then you started with, but in the meantime the money you paid for the seeds will be "locked up" in the growing crops (animals are another example; if you buy a cow it'll produce milk forever, but it'll take a while for it to pay for itself.) At the same time, when you're ready to buy more seeds you'll want to be sure you have enough to afford them, or you won't be able to plant as much as you want, and you'll miss out on a bunch of profit.

Loosely put, cashflow is a measure of when the money goes out and when the money comes in. A lot of this is keeping track of illiquid assets that haven't come due yet (e.g. crops that aren't fully-grown.) If you're very conservative with your spending it won't be hard to keep track of your cashflow, and you'll always be able to pay when you do need to buy something - but you won't end up making as much money as you could. On the other hand, if you aggressively leverage your money you'll need to keep a close eye on your cashflow to make sure you have liquidity when you need it. -

If you've been hanging around startup types enough you've probably heard a million times how important it is to scale and how hectic and demanding scaling can be. If this "scaling" is starting to sound more like a mythical harvest rite than a business concept, you can make it more concrete by scaling out your farm.

As you start making more money, you'll want to expand your operations so you can start earning even more. There are a lot of different dimensions you can scale along (some more worthwhile than others) and a lot of different resource bottlenecks you'll need to address at different times. For example:- You can only water plants at a certain rate, and this is a bottleneck on how many crops you can grow. If you want to water things more efficiently, you'll either need to upgrade your watering can (which allows you to water more tiles at a time) or buy a sprinkler (which waters the surrounding tiles automatically.) Both of these require ingots, which are made from minerals, which you have to get from the mines. Upgrading your can to higher levels/crafting better sprinklers requires rarer ingots (in ascending order of copper/silver/gold), and to get rarer minerals you'll have to go deeper in the mines (which also means you'll want to upgrade your pickaxe.) Oh, and don't forget you need to smelt raw minerals into ingots, which means you need to start to make a bunch of smelting furnaces, and provide a steady supply of coal to keep them going (which you can also get from the mines), and so on, and so on.

- Stardew has a community center that grants you special bonuses for trading in certain bundles of items. One of these is a greenhouse which is extremely important because it lets you grow crops during the winter. You can only get the greenhouse from the community center, so if you want it (and you do) you'll need to make sure you have the right items to trade in. A lot of the items to trade are crops that you can grow, but some only come from animals, so you'll need to build a barn and buy some animals before you can get the greenhouse. This means you need a bunch of cash on hand to pay for the barn, but you also have to supply the lumber, which means you'll need to cut down a bunch of trees. Might be worth upgrading your lumber axe to make that faster, but to do that you'll need ingots...you get the idea.

-

Scaling successfully in Stardew basically means building out and managing a whole supply chain. You won't need to go quite that far when scaling out e.g. a software business, but you definitely will need to focus on building out the appropriate capacities at the appropriate time: setting up the right marketing channels, hiring more finance/bizops/data/support/etc people, building out multiple offices, extending the product line, and so on. As in Stardew, you have many different dimensions you can scale along at any given time, and the right choice will vary based on the particulars of your company.

When you try to make as much money as you can in Stardew, what you get is a brief and gentle introduction to operations management, loosely described as "the process of efficiently turning inputs into outputs." A big part of operating well is sequencing your investments in a way that sets you up for success, deciding when to spend big on capital and when to focus on keeping the lights on, and picking just the right time to start scaling up your capacity. You can take this mentality as far as you want in Stardew - just find a hardcore player and ask them to show you their spreadsheets!

Learning from Smash Bros

If you’re unfamiliar with Super Smash Bros (often shortened to Smash Bros, or just Smash), it’s a famous series of fighting games where Nintendo characters beat each other up. The original Smash touted the transgressive appeal of watching Mario punch Pikachu in the face, but it was also phenomenally fun, and it kicked off a dynasty that spanned almost twenty years (Super Smash Bros Ultimate, the fifth and perhaps final installment, was released in 2018.) Smash was marketed as a casual party game, but its exciting gameplay and surprisingly deep mechanics also fostered a burgeoning competitive scene (the turning point here was the release of the second installment, Super Smash Bros Melee for the GameCube. Melee’s particularly heavy emphasis on furious, near-balletic movement made it ideal for high-level play - although interestingly it seems Nintendo did this by accident, given their subsequent chilly attitude towards the competitive Smash community.)

Expert Smash players focus on a lot of the same things more casual players do: things like mastering the mechanics, learning the intricacies of each character and stage, and building muscle memory through consistent practice. However, there’s one aspect of the game that’s only relevant for tournament play : the metagame (often shortened to the meta.) The metagame is the "game around the game", in which you attempt to predict how your opponents will play and devise a strategy that will effectively counter them. Given that in a tournament setting you don't have control over who you'll be matched against, understanding the meta means understanding in a general sense how the competitive community thinks about the game - what characters are regarded as strong/weak, what strategies are generally dominant, what situations people are trying to prepare for, etc.

Importantly, the meta is a moving target. Competitive players are constantly observing what works and what doesn't at various tournaments, as well as experimenting on their own. New developments get incorporated into the meta as they disseminate throughout the playerbase, and as everyone tries to leverage them to get the drop on their opponents (for modern games this process is often kicked off from the outside, as the devs patch the game to rebalance it and add new features.) The meta is reflective of the "wisdom of the crowd", in a sense, so it's quite difficult to get ahead of it, but on rare occasions there will still be blind spots. If you're lucky enough to discover information about the game that is not apparent to other players, you can leverage it to great effect (a powerful example of this is aMSa, a Smash player who became an expert on Yoshi - long written off by the community as an irrelevant low-tier character - and went on to win what was at the time the most competitive tournament in the game's history.)

What I picked up as I learned more about the Smash meta (and the metas for various other games) is that even in something as "straightforward" as a video game, excellence at the highest levels can be very situational. Some players are objectively better than others, of course, and there are certainly players who have a special ability to do well in every environment, but it's just as true that a strategy or play style that works in one meta can get crushed in another - and the meta is constantly shifting. In retrospect I kind of knew this already, and it's not a radical idea; there's a lot of talk, for example, about how dramatically basketball has changed in recent history (no one refers to this as the "basketball meta", but, y'know...they could.) Some of the titans of yesteryear may not fit in to the game as it's played today, and I think there's a broad recognition of this dynamic in every sport, as well as in tech, as well as in many areas of life.

My takeaway is: learn from the past as much as you can, but don't forget that no one has been in your exact situation at this exact moment in history, and no one knows for sure how to succeed in the future; we only know what it took to succeed in the past. This outlook might seem scary or dispiriting, but I don't think it has to be that way. It can also be pretty liberating to realize that the path to victory is yours to discover - and yours alone.

P.S. Most of what I know about competitive video games I learned by listening to YouTube videos in the background while I was (supposed to be) doing other work. If you'd like to know more, check these out (not sponsored or anything, I just like these guys and learned a lot):

- WolfeyVGC is a world champion Pokémon player who also spends a lot of time and effort making Youtube videos about his experiences. As a casual player I always thought Pokémon was easy (I just tanked everything with my Venusaur), but it turns out competitive Pokémon is nightmarishly complex, and Wolfey does a great job of breaking everything down.

- AsumSauce, who made that terrific aMSa documentary, has a lot of other great videos on Smash as well.

- I barely know anything about "classic" 1v1 fighting games and I'm really not good at them, but I stumbled on MoldyBagel's videos about Dragon Ball FighterZ and found them really interesting. Now I know a lot of cool fighting game theory (and I still can't apply any of it.)

Learning from puzzle games

Compared to the other genres on this list, "Puzzle Game" is a pretty fuzzy label. Pick up a puzzle game and you might find yourself deciphering arcane languages, setting up huge combos, picking apart an "unbeatable" platforming challenge, or hunting for clues on a mysterious deserted island. The best criterion I can muster is that a puzzle game tests your mental horsepower more than your fine motor skills (although even that's debatable.)

But I have to confess, I don't want to discuss puzzle games as a whole. I want to discuss Baba is You, a celebrated indie puzzler released in 2019 (did I write this entire post because I wanted an excuse to talk about Baba Is You, one of my favorite games of all time? Truly, who can say.)

Baba is a...goat?...that you can move around and push tiles with. There are different varieties of tiles that look like walls, water, fire, etc. and they have various rules tied to them; some are impassible, some act like conveyor belts, and some will vaporize poor Baba. These basic mechanics place Baba is You squarely in the Sokobon subgenre (named after a classic Japanese title about moving boxes around a warehouse); what sets it apart is that the rules governing the game are part of the game itself, expressed as sequences of tiles with English words on them, and you can activate, disable, or remix them by pushing their tiles around.

For example, every level contains the phrase "Baba Is You", to indicate that you, the player, are controlling Baba. If you rearrange the tiles to say "Water is You" instead, congratulations, you're a water tile. If there are multiple water tiles, you're all of them, and pressing the D-pad will move around the water instead of the now-inert Baba.

I play a few other puzzle games, but they don’t have a death grip on me like Baba is You. I think the “secret sauce” is that the game has very simple mechanics that interact with each other to produce an explosion of possibilities (it turns out Baba is You is Turing-Complete, so in a sense the search space is as large as it can be), which in practice means that there’s often no straight line from the structure of a problem to the structure of its solution. Put another way: playing Baba is You can be stressful, because there’s always the nagging worry that the solution uses a technique you’ve never seen before - maybe something that you didn’t even realize was possible!

Over the years I’ve found it useful to draw a distinction between what I’ll call Type 1 and Type 2 problems. Solving a Type 1 problem involves picking the correct techniques from your repertoire and applying them correctly. There's usually something in the problem that hints at the way to approach it (for example: "the solution to this problem depends on the solution to two smaller subproblems, so I need to use recursion or a stack.") It would be wrong to say Type 1 problems are easy - they can be a slog - but they’re more predictable. If they’re going to be difficult, you can tell right away, and you know what’s going to be difficult about them.

Type 2 problems, on the other hand, are more mysterious - they usually involve you getting from A to B however you can (for example, a mathematical proof starts with hypotheses and ends with a conclusion - what's in between is up to you.) These are "puzzle box"-style problems: they're easy to describe, but their very simplicity means they have a dearth of structural information that can clue you in on how to attack them. It’s hard to break down a Type 2 problem in a way that constrains the universe of solutions and tells you where to go next. It’s like having a nut you can’t crack - the problem feels solid and impenetrable.

I personally struggled with this aspect of Type 2 problems early in my academic career; the way I knew how to solve problems was highly methodical, deducing the answer by carefully analyzing the structure of the problem and proceeding from there. It was usually pretty frustrating to encounter a Type 2 problem in this context - here I had a seemingly simple problem that somehow refused to admit a simple solution. My instincts would keep telling me "well, it must not have a solution at all, then" but I was usually working on an exercise, so I knew for a fact that it did.

The first time I tried Baba is You I got stymied by the puzzles and quickly put it down. On my second attempt a year or two later I resolved to change the way I thought about the game. I had to unlearn my tendency to laser-focus on finding answers; what worked much better was a constructive approach, as opposed to an analytical one. I would start by listing out what I knew for sure, and then I would start experimenting, figuring out all the crazy stuff I could do in the level and proving all the facts I could, even if they seemed like they might not be relevant. I would slowly build up a body of knowledge about the problem in this way, putting out tendrils in every direction in the hopes of hitting something useful. This approach was very laid-back, almost contemplative - I was never entirely sure how I was gonna get where I was going - but eventually some key pieces would fall into place, and the solution would suddenly become clear, almost as if the problem had solved itself.

Alexander Grothendieck, titan of 20th-century mathematics, had a terrific quote about this kind of problem-solving that I think about all the time:

The first analogy that came to my mind is of immersing the nut in some softening liquid, and why not simply water? From time to time you rub so the liquid penetrates better, and otherwise you let time pass. The shell becomes more flexible through weeks and months – when the time is ripe, hand pressure is enough, the shell opens like a perfectly ripened avocado!

A different image came to me a few weeks ago.

The unknown thing to be known appeared to me as some stretch of earth or hard marl, resisting penetration… the sea advances insensibly in silence, nothing seems to happen, nothing moves, the water is so far off you hardly hear it.. yet it finally surrounds the resistant substance.

Life is full of Type 2 problems, and they aren't all puzzles or math problems. Many issues of strategy are Type 2 problems, for example, as well a lot of bleeding-edge technological questions.

Give Baba is You a shot sometime. I'll warn you up front you'll probably hit a wall after a while (the game has earned a reputation for being very difficult), but challenge yourself to push through - just remember to be creative, and don't try to force your way to a solution. It's a really great way to practice tackling Type 2 problems, and being able to "crack the nut", so to speak, is a rare and precious skill to have.

Learning from ???

I am just as aware as you of the elephant in the room - something that is obviously missing from this post, being as it is a list of video games drawn up by an engineer. Even as I write these very words, I can feel the anxious impatience of my future readers: “Factorio! Factorio!” they cry, “but what of Factorio?!”

Well, I haven’t played it yet. I’m sure it’s wonderful - people talk about it in rapturous terms - but to be honest I’m a bit scared that I won't be able to put it down once I pick it up. I do want to try it once I'm sure I'll have a bunch of hours to spare. When I do, I'll write an addendum with my thoughts!